Victoria versus the rest

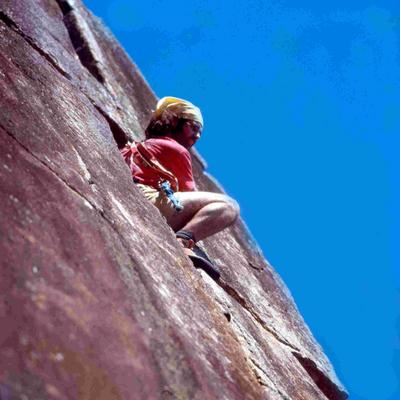

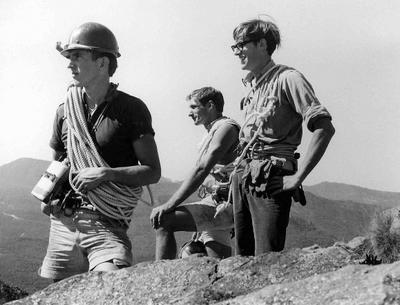

From the mid-1960s, the Sydney-based climbing magazine,

Thrutch, had become the main conduit for Australian climbers' ideas and opinions. And its policy of publishing almost anything provoked some lively debates which stirred along a growing rivalry between Victoria and the rest of the country. It was exacerbated in 1969 when Victorian climbers Chris Dewhirst and Chris Baxter spent two days on the north wall of Mt Buffalo in October 1969 to create

Ozymandius. They graded it M6 and claimed it as the hardest aid climb in Australia. Twenty years later, expatriate British climber Steve Monks would climb it

free, grading it 28. But back in 1969, it became the most publicised rockclimb in Victorian history, stemming from a newspaper photographer who happened to be staying at Mt Buffalo at the time. Meanwhile, John Ewbank and Bryden Allen returned quietly to Bluff Mountain in the Warrumbungles in October to complete

Stonewall Jackson. The 290 metre long route was probably the hardest and most serious yet climbed in Australia. Fresh from his Warrumbungles’ success, Bryden Allen then made the second ascent of

The Janicepts at Mt Piddington in November that year with Roland Pauligk making the second ascent of Victoria’s

Blimp at Bundaleer.

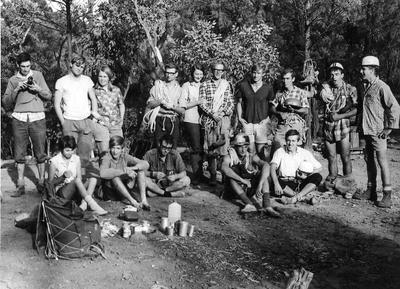

Beaks on the peaksIt was a time, too, when climbers from Victoria were making their mark internationally with Michael Stone, Ian Guild and John Fantini having successful seasons in the European Alps. The interstate 'war' wasn't confined to the letters' pages in

Thrutch. Out on the rock, the rivalry was as intense as New South Wales climbers Keith Bell and Howard Bevan discovered. They were making the 4th ascent of

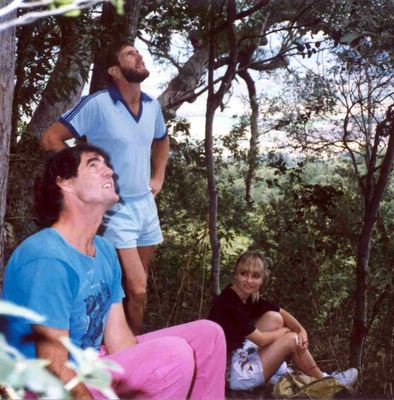

Lieben in the Warrumbungles with a gaggle of Victorian climbers watching, including Roland and Anne Pauligk who always travelled with a flock of their pet parrots. As Bell reached the crux of the climb, one of the birds flew up and landed on a ledge next to him, creating a dilemma: each time he stretched for the crux handhold, the parrot nipped at his fingers. It seemed that even the birds had decided which side they were on!

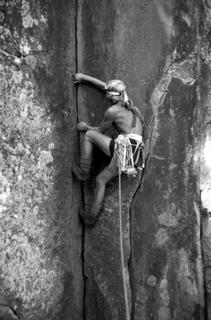

Internal exileIn the climbing press, Rick White constantly extolled the virtues of Frog Buttress—and any climbing area in Queensland, for that matter—stirring along the public relations’ battle with Victoria. White once told readers: ‘Frog Buttress is without doubt the greatest and most exclusive crack climbing outcrop yet visited by climbers on the Australian mainland!’ And, of course, he was right! His main sparring partner was Chris Baxter who visited Frog Buttress and admitted to his Victorian disciples that it was, indeed, a climbing destination of significance. Baxter recalls the era with a wry smile:

Initially there was the absurd interstate rivalry between Victoria and New South Wales and Victoria and Queensland and a lot of that was due to the lack of contact. It was childish on all sides. I suppose it was taken seriously and the letters would fly back and forwards through Thrutch and that would trigger it off. And there’d be raiding parties down to free Victorian routes or free NSW routes or whatever it was...

While much of the debate through the pages of

Thrutch was tongue-in-cheek, it got to a point where bitterness began to creep into the exchanges. White recalls the impasse: ‘There was a point in time where I made a decision never, ever to write another article—ever! I didn’t break that pledge until probably around 1996 when Chris Baxter talked me into writing a history of something or other for

Rock magazine. So I didn’t write anything from probably 73 onwards.’ Eventually, Victorian climber Nic Taylor who was working with White's company,

Mountain Designs in Brisbane, was instrumental in bringing them together in the late 1970s and they subsequently became good friends.

Illustration: Thrutch logo.