This site is an archive of documents, images, interviews and other information relevant to the origins of climbing in Australia. Comments are welcome (meadowsmh@gmail.com). Text copyright 2024 M.Meadows. Copyright to photographs is held by named photographers. Please request permission to reproduce.

Friday, September 09, 2005

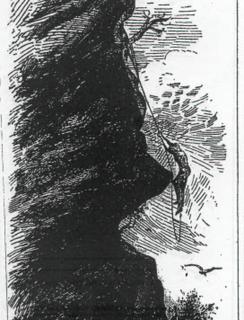

Brisbane adventurer and writer Thomas Welsby wrote the first detailed description of climbing the southwestern face of Tibrogargan (far left), one of the curious Glass House Mountains north of Brisbane, in 1886—although it probably was not the first ascent of the mountain. Welsby later published a book of his collected writings, The Discoverers of the Brisbane River, in 1913—the first to feature climbing as an activity. On his Tibrogargan attempt, Welsby was with two companions—‘one a muscular friend, the other a gentleman well acquainted with bush life’. Soon, Welsby found himself climbing alone and after casting off spare clothing and footwear, reached the summit. Keen to celebrate his success, he collected wood and started a fire, sending ‘great volumes of smoke curling upwards’ as a signal to the residents of a nearby accommodation house, west of the mountain. The fire spread across the entire mountain and that evening, Welsby and his companions watched the spectacle from the verandah of his lodging house. He wrote: ‘The moon did not rise until 8 o’clock. By that time, the place was all aglow, and as the moon rose from out of the eastern sky and threw its flooding rays over the hilltops, the blending of the two lights mellowed the scene with a ‘dim religious’ colouring of beauty none of us can ever forget.’

Picture: Michael Meadows collection.

Epics on Mt Lindesay

Epics on Mt LindesayPerhaps the most interesting aspect of these early ascents of peaks in the southeast is that there had been a philosophical shift from exploration as the impetus for climbing to something else. But it was almost 20 years until the third ascent of Mt Lindesay—and the most dramatic. On a cold July morning in 1890, 26 year old immigrant Norwegian naturalist Carstens Egeberg Borchgrevink sweated up the approach ridge with climbing partner Edwin Villiers-Brown, from nearby Beaudesert, and a third man, had agreed to join him on what they believed would be the first ascent. They carried with them ‘a manilla clothes-line about 25ft long, a tomahawk, and our sandshoes’. Borchgrevink and Villiers-Brown climbed to the base of a short steep rock pitch with a 70 metre drop below them where Villiers-Brown, ‘being the lighter of the two’, took the lead. He was instantly in trouble when a huge loose block of rhyolite pulled away, as Borchgrevink recounted: ‘Only his great presence of mind saved him. Quicker than thought, while sliding down he caught his fingers in a narrow crack, and so supported himself till he got a new hold. Eventually he got over and let down a string.’They struggled onto the scrub-clothed summit in the late afternoon light, shook hands, and realised there were no views. With the light fading, they began their descent. With one end of the rope tied around his chest, Borchgrevink began lowering himself over an overhang when he felt ‘a strange weakness’ in his arms: ‘My fingers gave way, and I held on to the rope with my teeth; but with them I could not carry my weight, and I felt that I must drop,’ he recalled. ‘My hands would not move to my assistance. What could I do? I dropped straight down, thinking “this will be my goodbye to the world.” The line, however, tightened under my arms, a creeper caught one of my legs, and for the moment I was safe.’ Their exploits were captured by artist Bihan in local publication, the Queenslander (above). The plucky Norwegian survived his Mt Lindesay ordeal and in January 1895, became the first person to set foot on the Antarctic continent.

Illustration: The Queenslander.

Assault on Mt Lindesay

Assault on Mt LindesayThe Badjalung people had many stories about Mt Lindesay (they called it Jalgumbun) designed primarily to discourage Indigenous people from climbing the mountain, but it seems almost certain that some either ignored this or had permission to make the ascent. Stories of Aboriginal people climbing the mountain were common in the district. Evidence suggests that Mt Lindesay was first climbed by Europeans sometime between 1846 and 1848, well before the claimed first ascent reported in local Queensland and New South Wales’ newspapers in 1876. It seems highly likely that it was the Queensland Collector of Customs, William Thornton, one of the Kinchela brothers—either John or James—and a third unnamed man, who reputedly used large vines hanging down the cliffs to gain the summit. A huge bushfire swept through the district shortly after the first claimed European ascent. On the second ascent of the mountain on 9 May 1872, local pastoralist Thomas de Montmorency Murray-Prior and Peter Walter Pears, a tutor, climbed what is now the tourist route on the mountain’s southeast corner.

Illustration: The Sydney News, 1886.

‘Embosomed in mountains of indescribable splendour’:

the 1st ascent of Mt Warning

Known by the Bandjalang people as Wollombin, Mt Warning’s first recorded European ascent was in 1871 by four local men—including botanist, author and landscape gardener William R Guilfoyle. He described their three and a half day climb, including the ‘almost perpendicular’ final 100-200 metres to the summit, where the climbers were spellbound: ‘We were so enchanted with the scenery that we forgot we had to descend until it was too late, and although we had left our provisions at the camp below, there was no other alternative than to stay for the night. This, however, was scarcely regretted, for we afterwards enjoyed the finest sight of which it is possible to form an idea. When the sun was declining massive clouds rose above the horizon and passed to the south-east at about 300 feet below us. As he sank they gradually diffused themselves and became tinted with every imaginable hue, representing a vast lake studded with islands of molten gold, and embosomed in mountains of indescribable splendour. At length those clouds again slowly rose and that glorious scene like a beautiful dream passed away, absorbing, as for a time, in a grey mist, which night overshadowed with its dusky grandeur.’

1st ascent of the 'highest mountain in Australia'

The 1820s heralded the beginning of the era of mountaineering in Europe that would see virtually all major Alpine summits climbed within 50 years. At this time in the colony of New South Wales, a penal settlement had been established at Moreton Bay. The first extracts from Moreton Bay penal settlement commandant Patrick Logan’s journals were published in Australia’s first newspaper, the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, in 1827. It was the same year that Logan stood at the top of a cliffline (Frog Buttress) on Mt French in southern Queensland, looking across the plains of the Fassifern Valley. Just after midday on 3 August the following year, Logan clambered barefoot onto the summit of what was then the highest peak in the colony, Mt Barney, 100 kilometres southwest of the new colonial outpost of Brisbane Town. As the 36 year old explorer gazed through the clear air, his two climbing companions, botanists Allan Cunningham and Charles Fraser, languished far below on a ridge that now bears his name. The traditional owners of the country here, the Yugumbir, called the massif Baga Baga. It was one of many places in Yugumbir country where people were either discouraged or forbidden to go. But expedition guide Logan knew little of this local law—his primary interest was in looking for new pastures for settlement—but was that the only reason he climbed to the highest-known summit in Australia that day? As Logan and the two botanists, accompanied by two unnamed convicts, reached the first rocky outcrops on the ridge, they gazed across the huge east wall of the mountain in awe of its ‘really terrific appearance, being a perpendicular mass of rock, unvaried by even the smallest trace of vegetation, except a few straggling lichens’. At the top of a pinnacle on the ridge, they were in for another shock—the summit of Mount Warning some 50 kilometres to the southeast protruding above the McPherson Range. All of them except Cunningham had believed it was Mt Warning they were climbing! Despite this discovery, Logan insisted on continuing, as Fraser later recounted in his journal: 'On a careful scrutiny of the fearful precipices which overhung us, Capt Logan detected a path by which it appeared possible, and barely possible, to ascend, so, putting off our shoes and stockings, and leaving the rest of the party behind, he and I began scrambling on hands and knees to the first peak, a height of about 300 feet, with great difficulty, but having once attained a certain elevation, we had no alternative but to proceed, any attempt at returning in this direction appearing totally impracticable.' At a point further up the ridge, Fraser turned back, leaving Logan to continue onto the summit alone. While the two botanists’ journal entries of the day’s events ran into many pages, Logan’s summary of his climb was just 200 words. At first, Logan named Mt Barney, ‘Mt Lindesay’, and today’s Mt Lindesay, ‘Mt Hooker’. Both names were changed to their present day titles in the 1830s, causing confusion well into the 20th century. Ironically, standing on the summit of Mt Barney that day, Logan would have looked into the Brisbane River Valley, hardly realizing that he would meet his death there two years later, speared most probably by local Aboriginal people. Two years after Logan’s death, a report by Cunningham, read to the Royal Geographical Society of London, relegated the details of the first European ascent of the highest known peak in the colony to a footnote, with Logan’s name omitted. Two years later in 1834, a scientist collecting geological and botanical specimens in the Australian Alps, Dr J. Lhotsky, most probably stumbled across the highest point in the colony although it was not named Mt Koscuisko (2228 metres) until several years later.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)