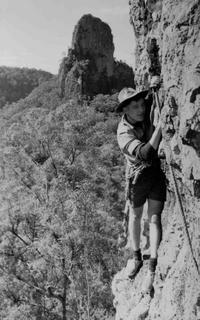

The 1st ascent of Boonoo Boonoo Falls

By 1956, climbing was expanding around Australia with activity in Bungonia Gorge, the Wolgan and Capertee Valleys, Lithgow, Frenchman’s Cap, Federation Peak, and the Glasshouses. Kippax returned to the Breadknife in the Warrumbungles climbing the North Arete with Dave Rootes, Jeff Field and Peter Harvey. That year, the first traverse of The Breadknife was done. Further north, Bill Peascod joined with local climbers Donn Groom, Neill Lamb and L Upfold to put up two new routes on the big south face of Beerwah in the Glasshouses—Pilgrim’s Progress and Mopoke Slabs. While Peascod’s influence on local climbing culture in Queensland was clear, several strong local climbers had emerged. Neill Lamb joined with Julie Henry and Frank Theos, starting the year by climbing the 180 metre high Boonoo Boonoo Falls—calling it the Belvedere Route. Lamb recalls the experience:

I remember when we climbed up the side of Boonoo Boonoo Falls, which had never been done, we just did that on the spur of the moment. It wasn’t a hard climb. The waterfall was thundering down one side of you and the holds were just there and the situation was just magnificant. You’re just there in some of these positions and the goose pimples come out…

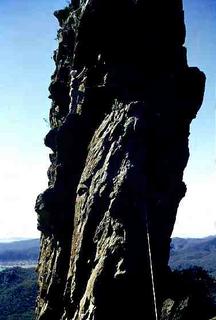

The 1st ascent of Prometheus II

Neill Lamb, 19, and Graham Baines, 18, joined up with Julie Henry, 38, Bill Peascod, 36, and his young son, Allan to climb an exposed new route on the east face of Tibrogargan, across the top of Cave Four. Baines was climbing last, this time, and recalls events when he reached a stance below a corner above the cave:

I had a clear view of Neill on the wall above, grappling with almost non-existent holds, his toenails curled over and clinging to rugosities on the rock face. He drove in a piton, to which he attached a carabiner to serve as a running belay. This gave him a slight feeling of security but he still could not progress and returned to the stance where Bill was belaying him. Bill moved out across the face to have a go at it. He had the same trouble as Neill and after a long battle, he, too, returned to the belay stance where he rested and thought things over. As yet undefeated, Bill gave it another go and, after poising precariously on the skyline for about ten minutes, he traversed to the left and disappeared from view. The rope moved forward spasmodically and we knew that he was getting somewhere. We heard a piton being driven in. Then a shout. Bill had mastered the pitch.

Lamb followed and it was clear that Peascod’s son, Allan, would not be able to climb it so Peascod lowered some ropes and slings and the young boy was trussed up in a bosun’s chair and literally hauled up the pitch. Julie Henry was next and she soon ran into trouble and was ‘winched’ from above by Lamb and Peascod.

Picture: Neill Lamb on the 1st ascent of Boonoo Boonoo Falls, 1956. Neill Lamb collection.