East Crookneck free

East Crookneck free...almost

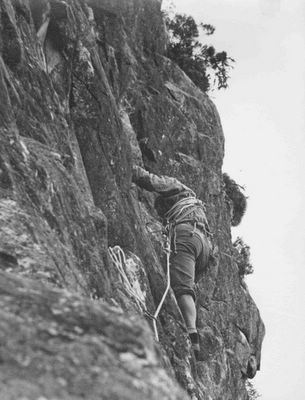

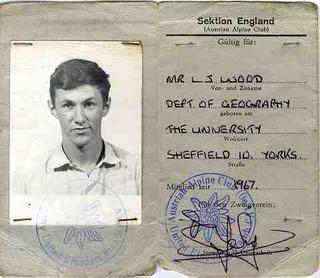

Perhaps the piece de la resistance for Les Wood (pictured) during his 1966 sojourn in Queensland was making the first (almost) free ascent of East Crookneck. Swinging leads with Donn Groom, they used some aid on the first pitch and then another aid move to climb the last big overhang on the second pitch. Les Wood continues the story: ‘We found most of it could be climbed free and that the etriers were necessary in one place. Much of the climbing was wide bridging around overhangs and the last pitch was done in very heavy rain.’ Shortly after the climb, Wood teamed up with Ted Cais who led an all-free version of the first pitch. The first free ascent of the climb was made by Greg Sheard and Chris Meadows in June 1968. Crookneck's southwest buttress was another problem that attracted the attention of Les Wood and Ted Cais in 1966. They started a new climb there that would eventually be called Flameout:

My first attempt was in August 1966 with Les Wood but he backed off the second pitch realizing this would probably be the first VS [Very Severe] in Queensland. So I returned in the heat of November with Donn Groom and he passed the overhang that was Les’s previous high point with two points of aid but took a whipper on an upside-down peg—it held—before figuring out the thin moves above. For a while this was indeed the hardest route although John Tillack claimed an equally difficult climb named Medusa on the organ-pipe columns somewhere on Beerwah’s northwest flank.Donn Groom and Ted Cais were emerging as the strongest and most consistent leaders amongst the cohort of Queensland climbers of the mid-1960s. In July, Groom teamed with long time friend John Larkin to climb Alcheringa on the vertical rhyolite columns of Binna Burra’s east cliffs, again vying for the hardest climb in Queensland. Cais later made the first free ascent, eliminating the few aid moves. Cais played a key role in the last new route climbed by Les Wood during his Queensland stay by solving the tricky first pitch puzzle on Overexposed. Wood and Groom joined forces again to complete the route which offers sensational, exposed climbing through a series of small, shallow caves on the southern edge of the summit overhang on Tibrogargan. In the pre-cam and hex days, there was little protection on the route but modern equipment has helped to make it less psychologically challenging. Nevertheless, the aura surrounding the climb has meant that it is rarely repeated.

Picture: Les Wood-Donn Groom collection.