Climbing with 'the spiritual father'

The following edited account was published in the Italian Alpine Club journal, Lo Scarpone, in 1953. It is written by the former Italian Consul in Brisbane, Felice Benuzzi, a climber and author, who here describes his climbs in the Glasshouses with Bert Salmon in 1950. The translantion is by Dr Claire Kennedy of Griffith University.

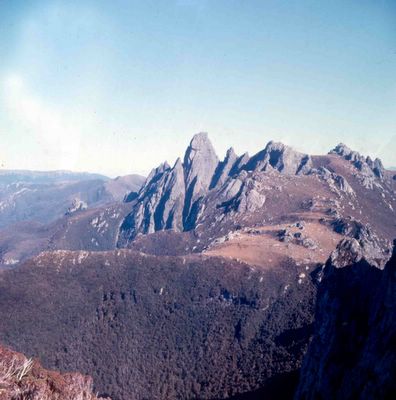

Sea travellers who leave Brisbane with its flowering gardens, and Moreton Bay, infested with sharks, and turn north once at sea will see rising out of the mainland on the left a series of 10 very strange peaks, each one separate from the other. Captain Cook, who was the first European to see them about 200 years ago, called them the Glass House Mountains because they brought to his mind the outlines of glass houses in Yorkshire. I have never visited the glass factories in Yorkshire and I don’t know why they have such a curious form. These peaks that burst into the sky from the plain—one here, one there, as if by a very peculiar caprice on nature’s part—are different in form and height but none is higher than 500 metres. Beerwah, the highest and the easiest, has a pyramid shape with a rounded-off peak like a kind of crooked beret and vaguely resembles the Antelao.

‘Pity’, says Bertie, ‘that it’s not 2000 metres higher. What a beautiful mountain we would have close to the city. And up there, wouldn’t a little glacier be at home?’

‘I agree’, I answer, ‘but what would the pineapple growers have to say about having a glacier flowing under their feet. They’d have to change their trade.’

As the car travels along the road through a monotonous forest of eucalypts, we can see the other peaks. The nearest one is Tibrogargan—massive and round with red-brown rock in the first rays of the Spring sunshine. And further on, the absurd Coonowrin or Crookneck, that rises up from a conical base to look like the bell tower in the Campanile di Val Montanaia in the Dolomites. Bertie knows all these mountains like his own pockets. He’s been coming here for 30 years, off and on, in good weather and bad, and has explored all the faces. He’s bivouacked under the sheer cliffs and has taken up hundreds of young climbers in south Queensland who see him as an expert and lovable guide—a kind of spiritual father.

‘How is it,’ he said to me when I met him, ‘that you’ve been in Brisbane for almost a year and with your passion for mountains you haven’t yet been on the Glass House Mountains?’

‘I was waiting to go there with Bertie Salmon,’ I replied. ‘And now here we are.’

[…]

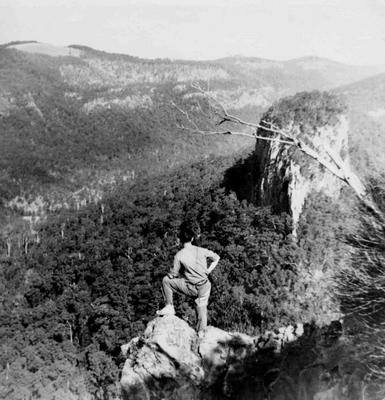

We arrive at the face of the virgin east wall of Crookneck that from close-up, looks like the petrified spray of a giant fountain. The layers fanning out reinfoirce this impression. It’s not stuff for our teeth—at least not today. The shadows are longer when we start climbing the usual route from the south. Spiny bushes sting our hands and the rock is crumbly. Bertie suggests a more interesting and direct variant where I realise very quickly that I am out of condition. The last time I touched rock was a year and a half ago at the rockclimbing school at Fountainbleu. ‘Damn old age!’ I stammer in Italian. In anger, I throw away into the empty air the holds that come off in my hand one by one. Bertie laughs and I have to draw on all of my national pride to keep up with the agile and thin Australian 50-year-old. The wall of the so-called variant is no higher than 25 metres and soon we are again on the usual route that takes us easily to the crest, free of vegetation, and onto the summit marked by a trigonometric structure visible from below.

The sun setting in a cloudless sky illuminates an enchanted panorama of nearby peaks with their strange Aboriginal names with meanings unknown even to Bertie—Tibrogargan, Beerwah, Ngungun, Tunbubudula Twins, Ewan, Miketeebumulgrai. Who knows? Maybe the Aborigines had legends and traditions linked to these mountains? But who would know them? They stand on a vast plain, covered by dense forest, interrupted here and there by cultivations of pineapples and the distant Pacific, now the colour of lead. Bertie extracts the summit log book from its cover and passes it to me. I open it curiously. What do these mountains say to those who were born and who grew up in this land?

On the first page there’s a memoir of the first climber, Henry Mikalsen in 1910, and a newspaper cutting of the time that describes that victory, that climb, in ingenuous and picturesque words. In the following pages I find the signature of my companion at least 20 times. Many are nocturnal ascents by the light of the moon via the usual route from the south; not many climbs from the west; and those from the north you can count on one hand. At least there are not those political references that abound in our summit log books and refuge books. There’s no ‘viva o morte’ [‘long live…’ or ‘death to…’]. Blessed Australia! But the usual stupidities confirm for me that humanity in the antipodes is not so different from those in the Alps or the Apennines. ‘We are the three musketeers’, write three young people. ‘If you want trouble, come to us!’ And their signatures and addresses follow. Two young immigrants apologise if they’re not yet able to express themselves in English and describe their enthusiasm in moving tones of German. No Italian names.

The sun is close to setting as we descend by the north face. Here, according to the summit log book, a solitary climber, thinking he was grasping a piece of jutting rock, instead grabbed the tail of a carpet snake—not a poisonous snake, fortunately, but eight feet long. Only at one point it is a bit delicate and we have to use the rope and after a brief but enjoyable climb we are at the base. The forest is quieter than ever now. The sky has become the purest colour of apricot. From a farm we can hear a woman singing as coming from another world. When we get to the car, in the infinitely clear night sky, the Milky Way blazes like the whoosh of a cold flame.