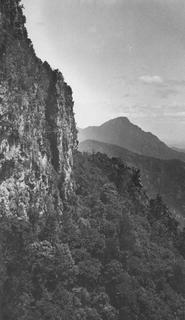

The challenge of the Fly Wall

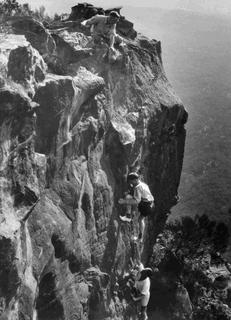

The challenge of the Fly WallNew South Wales identity Dr Eric Dark (pictured at the top of the cliff) headed a small group of local climbers called the Blue Mountaineers. As the name suggests, the Blue Mountains west of Sydney were their playground. The group, also known as the Katoomba Suicide Club, had devised a test climb that all new members had to complete before being allowed to join. It was up a steep, eight metre sandstone wall—the Fly Wall—and the Queensland contingent visiting the area in 1934 was champing at the bit to have a go. But there was a problem—Eric Dark insisted they use a rope tied around their chests as a belay. ‘I put the rope on,’ Salmon recalled, ‘and then I took it off!’ Eric Dark, the president of the Blue Mountaineers, retorted: ‘You won’t!’ Ignoring him, Salmon replied: ‘I am going to try, anyway,’ and he started up the climb unroped, to the horror of the Blue Mountaineers looking on. ‘I tried my level best for Queensland and for my own reputation,’ Salmon said, ‘and I succeeded in climbing to the top of the wall without the rope. That was the first time it had ever been done! Dr Dark was amazed.’ Now it was Salmon’s climbing partner George Fraser’s turn. He dutifully tied the rope around his chest and started up the wall but after a few metres, the feisty Scot (pictured above) shouted, ‘Blimey, ‘I’m going to climb it without the rope, too!’ In true ethical style, he downclimbed to the base of the wall, flung off the rope, and climbed it ‘as surefooted as one of those mountain chamois that roam the Alps in Switzerland’. The Fly Wall was noted for its ‘rudimentary’ finger and foot holds and at one point, climbers had to jump for the next hold. A miss would have seen the Queenslanders injured or worse. Salmon and Fraser had shown-up the locals, perhaps the catalyst for the interstate climbing rivalry that persists today.

Picture: A. A. Salmon collection.