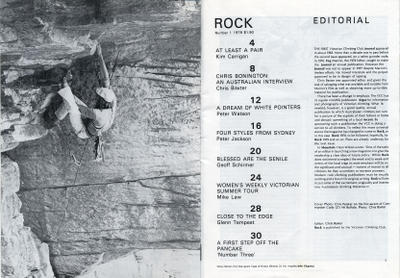

Climbing by numbers

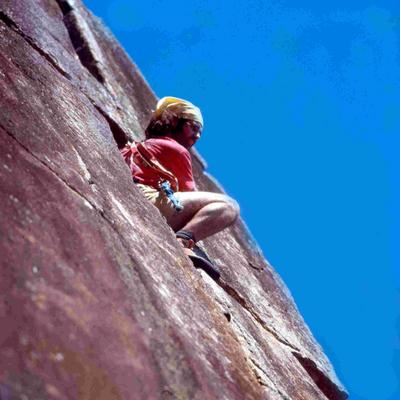

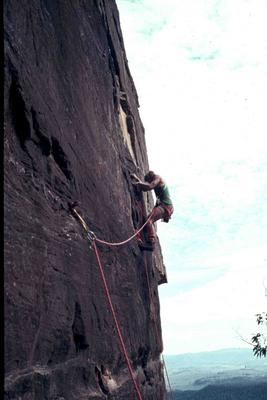

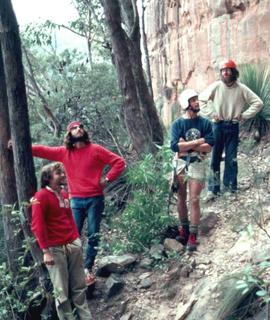

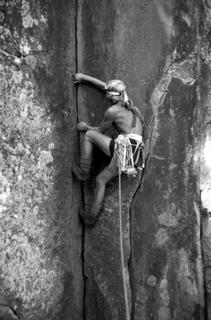

In Australia by the mid 70s, another generation of young climbers was filling in the gaps at Frog Buttress and various other crags around the country. With Rick White pursuing his business interests in Mountain Designs and other climbing projects, this cohort was a lot more mobile than in previous eras and many moved from crag to crag, picking off the prime routes as they pushed the upper limits of the possible. It included Greg Child, Chris Peisker, Kim Carrigan, Mike Law and Nic Taylor. In January 1976, Taylor was the first to break from the pack, climbing Australia’s first grade 24—

Country Road, at Mt Buffalo. Peisker was hot on his heels and produced

Horrorscope at Mt Arapiles, a climb of equal difficulty. The gauntlet had been thrown down. Taylor spent almost a year in Queensland, much of it climbing with White. Then it was time for something special, as White recalls:

Nic and I hatched a plan to go to Mt Buffalo and simply blow everyone away by doing a hammerless ascent of Lord Gumtree. I guess we picked Lord Gumtree because it was the hardest, I had prior knowledge and we had not forgiven the uncharitable locals after our second ascent a few years earlier. Thinking back, it’s hard to justify hammerless climbing. Why make a hard aid route even harder by leaving behind some crucial gear? I guess as Lito Tejada-Flores would say it’s just another game climbers play. Pitches that were easy on pegs now became M7 and we weren’t at the crux rurp pitch yet! I led all the hard pitches with grades of M6, M7 and M8. When we finished, we ran into Roland Pauligk, whose home-made nuts had helped to solve the crux, and convinced him he should make a smaller size. Thus the RP size 0 was born.

One new face on the Queensland scene was Coral Bowman. The expatriate American spent some time working with Rick White in his growing Mountain Designs business but found time to make the hardest female ascents in the country, including

Insomnia and

Black Light at Frog Buttress. Two years later in 1978, she was regularly climbing the hardest routes graded then at 24—and put up a new climb at Maggies Farm on Mt Maroon,

Little Queen, grading it 22. Rick White teamed up with Greg Child in 1978 on the 10th anniversary of the discovery of the cliff to climb

Decade, and do the first free ascent of Impulse, grading it 24. Boundaries are there to be pushed and in April that year, Chris Peisker climbed Australia’s first grade 25,

Ostler, at Bundaleer in the Grampians. It was the country’s hardest climb for just five months—Kim Carrigan found

Procul Harum at Mt Arapiles in September, pushing the grade up to 26.

Illustration: The Mountain Designs logo designed by Vicki (Couper) Farwell in 1977.

East Barney solo

East Barney solo