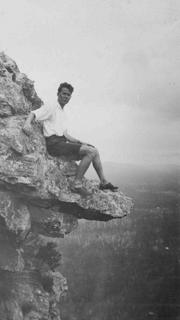

The 'spiritual father' of Queensland climbing

The 'spiritual father' of Queensland climbingAlbert Armitage 'Bert' Salmon was born in Queensland on the numerically-auspicious date of 9.9.1899 and started climbing while in his early 20s. He has often been referred to as ‘the spiritual father of Queensland climbing’ but his influence was much broader. He started the first climbing club in Australia around 1926 and made several visits to the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, in the early 1930s on climbing trips. He and New South Wales counterpart, Dr Eric Dark, are the pre-eminent figures in influencing the development of climbing in Australia between the wars (World War I and World War II). Salmon and his cohort most probably were influenced by the ethics of early British gritstone climbers like Dean Frankland and Fergus Graham, renowned for their preference for soloing climbs in the Lake District around this time. In the early 1920s, the modern system of using a rope to safeguard a leader on a climb was virtually unknown in Australia. Like many climbers at that time, Salmon believed that using a rope on a climb was dangerous, and he had a point—without a reliable belay, a falling climber attached by a rope to others would more than likely pull everyone off the cliff. Although many felt Salmon took this attitude too far, the dogged Queenslander made a point of emphasizing the lack of reliance on a rope in the numerous accounts of his exploits from the late 1920s until World War II. Australia’s first mountaineer, Sydney climber Freda du Faur, wore an ankle-length skirt when she made the first female ascent of Mt Cook in New Zealand in 1912 and this fashion persisted in Australia until the late 1920s. But within a few years, a remarkable change would free women, in particular, of the long garments that had plagued them from their very first steps into the mountains. Throughout the 1930s, women were climbing in shorts and sandshoes in Australia and setting the trend that continues, albeit with some modifications, to this day.

Picture: A. A. Salmon collection.