The 1820s heralded the beginning of the era of mountaineering in Europe that would see virtually all major Alpine summits climbed within 50 years. At this time in the colony of New South Wales, a penal settlement had been established at Moreton Bay. The first extracts from Moreton Bay penal settlement commandant

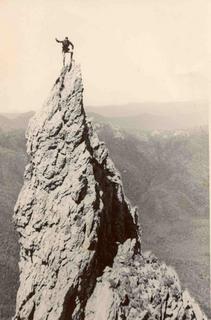

Patrick Logan’s journals were published in Australia’s first newspaper, the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, in 1827. It was the same year that Logan stood at the top of a cliffline (Frog Buttress) on Mt French in southern Queensland, looking across the plains of the Fassifern Valley. Just after midday on 3 August the following year, Logan clambered barefoot onto the summit of what was then the highest peak in the colony, Mt Barney, 100 kilometres southwest of the new colonial outpost of Brisbane Town. As the 36 year old explorer gazed through the clear air, his two climbing companions, botanists

Allan Cunningham and

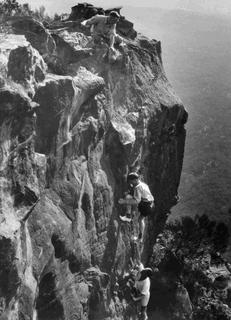

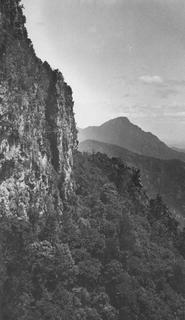

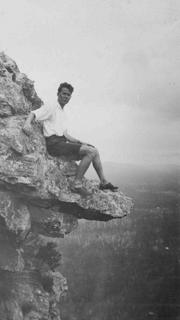

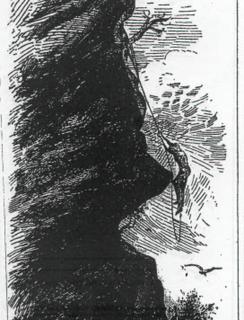

Charles Fraser, languished far below on a ridge that now bears his name. The traditional owners of the country here, the Yugumbir, called the massif Baga Baga. It was one of many places in Yugumbir country where people were either discouraged or forbidden to go. But expedition guide Logan knew little of this local law—his primary interest was in looking for new pastures for settlement—but was that the only reason he climbed to the highest-known summit in Australia that day? As Logan and the two botanists, accompanied by two unnamed convicts, reached the first rocky outcrops on the ridge, they gazed across the huge east wall of the mountain in awe of its ‘really terrific appearance, being a perpendicular mass of rock, unvaried by even the smallest trace of vegetation, except a few straggling lichens’. At the top of a pinnacle on the ridge, they were in for another shock—the summit of Mount Warning some 50 kilometres to the southeast protruding above the McPherson Range. All of them except Cunningham had believed it was Mt Warning they were climbing! Despite this discovery, Logan insisted on continuing, as Fraser later recounted in his journal: 'On a careful scrutiny of the fearful precipices which overhung us, Capt Logan detected a path by which it appeared possible, and barely possible, to ascend, so, putting off our shoes and stockings, and leaving the rest of the party behind, he and I began scrambling on hands and knees to the first peak, a height of about 300 feet, with great difficulty, but having once attained a certain elevation, we had no alternative but to proceed, any attempt at returning in this direction appearing totally impracticable.' At a point further up the ridge, Fraser turned back, leaving Logan to continue onto the summit alone. While the two botanists’ journal entries of the day’s events ran into many pages, Logan’s summary of his climb was just 200 words. At first, Logan named Mt Barney, ‘Mt Lindesay’, and today’s Mt Lindesay, ‘Mt Hooker’. Both names were changed to their present day titles in the 1830s, causing confusion well into the 20th century. Ironically, standing on the

summit of Mt Barney that day, Logan would have looked into the Brisbane River Valley, hardly realizing that he would meet his death there two years later, speared most probably by local Aboriginal people. Two years after Logan’s death, a report by Cunningham, read to the Royal Geographical Society of London, relegated the details of the first European ascent of the highest known peak in the colony to a footnote, with Logan’s name omitted. Two years later in 1834, a scientist collecting geological and botanical specimens in the Australian Alps, Dr J. Lhotsky, most probably stumbled across the highest point in the colony although it was not named Mt Koscuisko (2228 metres) until several years later.

Federation Peak

Federation Peak