Ghosts and The Glass Houses

The 300 metre high peak, Crookneck, in the Glass House Mountains north

of Brisbane was one of the last summits in Australia to be claimed by

Europeans. In 1886, Queensland explorer and climber Thomas Welsby described ‘a

great falling away of stone’ on the east face of the mountain. Seven years

later in 1893, the Royal Society of Queensland heard details of another

landslide revealing ‘a huge fissure’ following a sustained period of heavy rain

that caused massive flooding in Brisbane. And so the climb known today known as

East Crookneck was born.

But it would be more than half a century before climbers seriously considered

the east face as a possible ascent route.

The

mountain, called Coonowrin by the Kabi Kabi people, has always been

an object of fascination for Europeans. Towards the end of the 19th

century, speculation on the possibility of someone climbing the peak was

rife with

one local sage insisting: ‘It has always been said by old bushmen that

Crookneck cannot be surmounted.’ Another scribe in 1885 made a bold

prediction—curiously accurate, as it turned out: ‘I don’t doubt that

when the

railway makes these [mountains] within reach of the Brisbane tourist,

many will

try then ascend, but without engineering skill being brought to help it

will

not be done.’ Pragmatic local explorer William Landsborough simply

reminded them

that if the mountain was in England ‘it would have been climbed a dozen

times’.

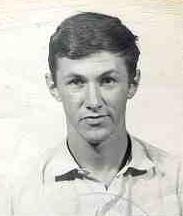

But it wasn’t until 1910 that 23-year-old local lad Henry Mikalsen (pictured above) made

the first ascent, solo, up the treacherous, loose north face. ‘The feat was not

accomplished without difficulty and danger,’ the Brisbane Courier reported. ’The trip took about three hours from

start to finish, and as his home is at the foot of the mountain, he was watched

with anxious eyes and could be seen the whole time.’ Pioneer climber Bert

Salmon always referred to this first ascent of Crookneck as the birth

of modern climbing in Australia.

Two years later, on Empire Day 1912, three sisters—Jenny, Sara and Etty

Clark—became the first women to reach the elusive summit, climbing a new route

on the southern side now known as Clark’s

Gully. It is one of the earliest recorded instances in Australia of the now

accepted technique of belaying. One of the Clark sisters tested out the system

unexpectedly, as this account of the climb suggests: ‘As she stepped off onto

another little corner the rock gave way and left her swinging for a moment in

mid-air, some 100 ft above the ground. Fortunately, the rope was good, and in

strong hands, and she soon gained a fresh foothold and she soon clambered into

safety.’ Etty Clark managed to get halfway up the climb, 36 years later, observing:

‘When I climbed to the top…we girls took off our skirts and finished the climb

in knee-length bloomers. They didn’t have shorts in those days.’

In the early 1920s, Philip Webster and his brothers, Tom, George and the

‘partially handicapped’ Norman, found a new climb on the south side of

Crookneck which follows most of the existing Salmon’s Leap or tourist route. Strangely, this is the only

climbing route in southeast Queensland bearing Salmon’s name, but it is one he

never claimed. During the 1930s, with climbing booming in southeast Queensland,

Crookneck was one of the favoured destinations. On one trip in September 1934, Salmon

took a record group of 26 people up the mountain, encouraged by the

irrepressible George Fraser playing ‘Highland airs’ on his bagpipes from the

summit! Around this time, Salmon and another 30’s stalwart, Cliff Wilson, made

an extraordinary first descent of

west Crookneck.

The first serious attempts to climb the east face began in 1950 when Bob

Waring and another University of Queensland student, Jim Gadalof, abseiled down

the fiercely overhanging route. They had no abseil devices—not even a

carabiner—adopting the classic method for the painful 75 metre descent. Waring

discussed the possibility of climbing the face with John Comino, a co-founder

of the University of Queensland Bushwalking Club (UQBWC). Comino abseiled down

to a small ledge, dubbed the ‘Eagle’s Eyrie’, and climbed what would eventually

be the last pitch of the route. But the real problem was what lay below.

This was the challenge for university

physics student Ron Cox who began his drawn-out project to climb the face in

June 1959. Cox read Guido Magnone’s 1955 book, The West face of the Dru,

and was inspired to apply the same techniques. ‘That was the great era of

artificial climbing in the Alps,’ Cox recalls, ‘and reading that and other

books and magazines I became very interested in artificial climbing which had

its apogee at that time. So that’s how we started doing that sort of thing.’ He

teamed up with UQBWC friend Pat Conaghan and the two set about making their own

gear for an attempt on East Crookneck—etriers and wooden wedges in Cox’s

father’s furniture factory, and pitons cut from steel plate. Cox recalls the

pitons were flat with no wedge: ‘I remember on one occasion going to a guy who

had a little forge in Margaret Street—unimaginable now—and I gave him some of

these pitons and got him to hammer a taper into them. I remember using one of

these on East Crookneck and the head snapped straight off!’

|

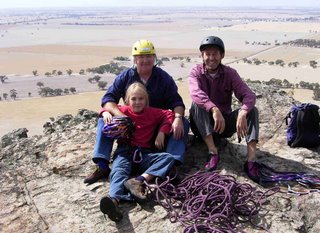

Ron Cox engaged in the assault on the east face of Crookneck,

The Glass House Mountains, 1959 (Pat Conaghan collection). |

Cox found ‘great piles of

ironmongery sitting at the foot of the cliff—big spikes, 30 cms long’— perhaps evidence

of previous attempts. Climbing on weekends and belayed by a range of partners,

Cox slowly advanced up the route over the next three months. ‘It was vertical: that’s

the essential thing’, he recalls. ‘And in a sense, to that point in Queensland,

we were climbing things that weren’t vertical that had a bit of a slope.’ It

was arguably the first serious application of double rope, aid climbing

techniques in the country. Although he had adopted the European approach, he still

imposed ethical limits, rejecting the use of bolts ‘because they made anything

possible’.

Cox had quickly established himself as one of the best—and

safest—climbers in the Brisbane-based cohort and had already made his mark on

the cliffs at Kangaroo Point, climbing the route now known as Cox’s Overhang

on a top rope, early in 1959. Described by Comino as ‘built like a bloody

spider’, Cox was one of the few at that time who could climb the overhang free.

The climb was probably the hardest in Queensland. Comino remembers being

impressed by Cox climbing the route and then being challenged to have a go

himself—on a top rope: ‘Anyway I got up there and after that I think Ron

thought, “Well, this fellow can climb” and that’s probably what caused him to

look me up about Crookneck some time later.’

|

| Pat Conaghan bivvying during the first ascent of the east face of Crookneck in 1959 (Pat Conaghan collection). |

Following his

7th attempt on East Crookneck and with just 25 metres of the route left, Cox decided

it was time for a first ascent push. He asked Comino to come out of retirement

to join Conaghan and himself and the trio gathered below the face on 18

September. Cox reached his previous high point in about three hours and called

for Comino to follow. Conaghan described the experience in the 1960 edition of

the UQBWC magazine, Heybob: ‘Comino

had not climbed artificially and for a while was floundering in the

technicalities. Adjectival phrases floated down consistently and at one stage,

having already discarded his hat, he threatened to throw his etriers away too.

He was soon, however, heard quietly praising the possibilities and efficiency of

these mechanical contrivances and by late afternoon had joined Ron on the

ledge.’ The stance was just big enough for two people and with the light

fading, Cox and Comino set up a bivvy. ‘I retired to my own little protected

ledge under a large roof near the start of the climb,’ Conaghan recalls.

‘During the night, heavy showers of rain carried by a N-W wind fell. I wondered

if the boys were getting wet on top.’

Cox began climbing the final

pitch at 11.00 am the next morning, as Conaghan describes it: ‘First up the crack,

then out onto the wall, then back into the crack again. A piton here and there

was needed but progress was fairly quick for this face—25 feet an hour. So the

gap between Ron and the top narrowed.’ Conaghan dozed and was woken at 1.30 pm by

the sound of some big blocks crashing down as Cox cleaned out the exit chimney.

He crawled onto the summit ridge at 1.55 pm.

In these pre-jumar days, it was

almost dark by the time Conaghan reached Comino on the last stance and with a

torch dangling around his neck, Conaghan kept climbing: ‘Ron yelled directions

from above—where to look for the next piton, or find essential holds. A flash

of my torch would reveal the route for the next few feet, then followed moments

of fumbling for holds as the torchlight danced fitfully, at waist level.’

Conaghan recalls the moment he reached Cox on the summit ridge: ‘A cold wind

was blowing on top and the night was crystal clear. Stars sparkled brilliantly

and a full moon was just rising from the ocean.’ Comino, ‘festooned in a tangle

of rope, etriers, wedges and links’, soon joined them and they scrambled up the

last 20 metres to the summit together. Their entry in the log book read: ‘First

ascent East Crookneck—8th attempt—40 pitons, 7 wooden wedges—last

man up at 8.30 pm.’ Conaghan recalls they had some trouble finding the path

down Salmon’s Leap but there was

another reward on the descent: ‘A huge gleaming mass stood out against the

western sky. It was Beerwah, lit by a silver moon.’

Despite the epic nature of the climb,

it was a significant achievement, although Cox remains circumspect about its

impact: ‘I felt very elated doing it and very embarrassed in retrospect at not

having done it cleanly at all. I guess I could have done it more cleanly but at

the time we were not aware of purer forms of climbing. We just went up and

looked at it. I would say I learned to climb on East Crookneck which is not the

ideal place to learn to climb. Since we couldn’t climb very well we took a long

time to get up.’ In 1961, Cox repeated the route with Peter Hardy, a member of

Rhum Dhu, a radical offshoot of the Sydney Rockclimbing Club. On a top rope,

Hardy managed to climb much of the second pitch free using the chimney, rather

than following Cox’s original peg line on the left hand wall.

But it remained essentially an

aid route until expatriate British climber Les Wood’s visit to Queensland in

1966. His impact on raising standards in Australia at that time was similar to

that of a young Sydney-based climber called John Ewbank. One of Wood’s first Queensland

targets was East Crookneck, urged on by his close friend and climbing partner,

Donn Groom. ‘We found most of it could be climbed free and that the etriers

were necessary in one place,’ Wood recalls, consulting his diary. ‘The last

pitch was done in very heavy rain. Three and a quarter hours. A good route. I

remember Donn saying that he thought this was one of the big challenges in the

Glasshouse Mountains.’

The last aid move on the climb—at

a huge bell-shaped overhang—was eliminated by an energetic Greg Sheard and

Chris Meadows in 1969. But another challenge has loomed: five years ago all

climbing on Crookneck was officially banned—allegedly for ‘safety’ reasons. But

strangely, voices can still occasionally be heard drifting down from the

heights on Crookneck—perhaps those of the ghosts of climbers past, determined

to keep alive the spirit of adventure on this memorable crag.

(First published in the Australasian Climbing Journal, Crux Number 2)