The swinging sixties

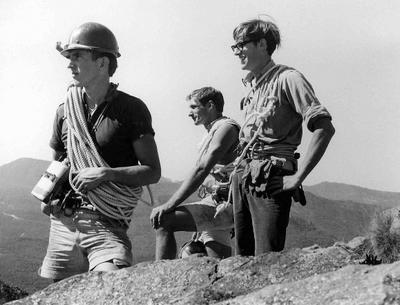

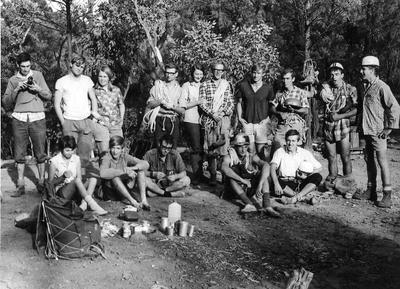

Climbing in Australia went through an extraordinary period of development during the 1960s. As Queensland entered a period of calm, in New South Wales, there was a shift from the longer ‘adventure’ climbs to shorter and harder routes. The Sydney University Mountaineering Club formed in 1960 and initially started developing Narrowneck as a climbing destination. Around this time, a team of climbers from the Victorian Climbing Club made an assault on Tasmania, climbing the east face of the Foresight on Mt Geryon. Back on the mainland, they climbed classic routes like Buddha’s Wall and The Cat Walk in the Grampians, followed up in 1961 by two bold routes on Federation Peak — the Northwest Face by Bob Jones, Jack O’Halloran and Robin Dunse, and The Blade Ridge, climbed again by Jones and O’Halloran.

Sandshoes and steel

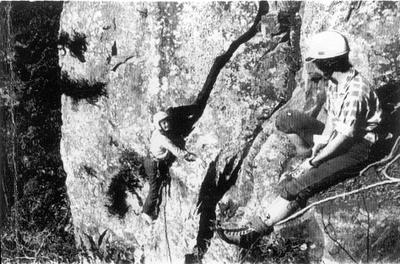

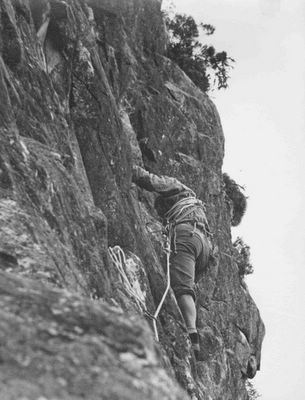

At the start of the 1960s, the vast majority of climbers in Australia still used the redoubtable Volley OCs as footwear, hemp rope, mild steel carabiners, pitons and — increasingly in New South Wales and Victoria — expansion bolts. Climbers in New South Wales in 1960 had begun to seriously investigate the potential of expansion bolts as a form of protection on the friable sandstone cliffs in the Blue Mountains. It provoked ‘strong feeling’ over their use—and a long and continuing ethical debate—although as protective devices they have become a central element of modern rockclimbing globally. Existing rockclimbing clubs in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane experienced a dramatic increase in membership in the 1960s, although the overall numbers of core climbers remained small, particularly in Queensland. By 1961, rockclimbing had split into two categories in Australia: free and artificial or aid climbing. Nylon ropes were becoming more common, along with advice on the best boots for rockclimbing, costing between £4/6/0 ($9.00) for a pair of RLs (Robert Lawrie) or £6/-/- ($12.00) for a pair of PAs (Pierre Allain). This description is from a 1961 MUMC catalogue:

The desirable features of a boot for rock climbing are narrow and slightly pointed toes, rigid and almost flat soles flush with the upper, with little or no protruding welt, low cut ankles, and a comfortable fit.

Perhaps encouraged by all the foreigners snatching local routes from under their noses, Tasmanians formed their own climbing club early in 1962. Across Bass Strait, the first climbing guide to Victoria was published, listing 15 routes. Fewer than 12 climbers were in action there but one figure soon stood out—Peter Jackson. Over the next few years, he was rarely far away from the cutting edge routes being climbed. And, like their Queensland colleagues, several Victorians were drawn into mountaineering imbing in the Alps and the Dolomites at this time.

The return of Bryden Allen

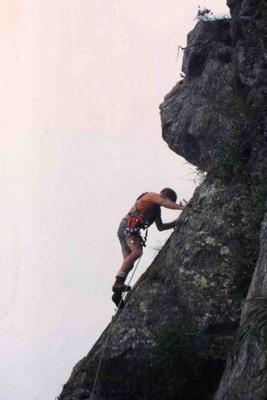

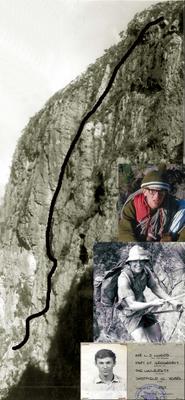

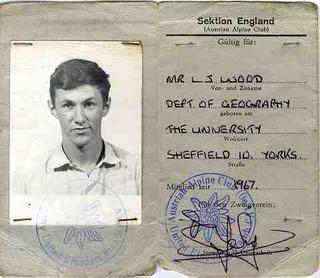

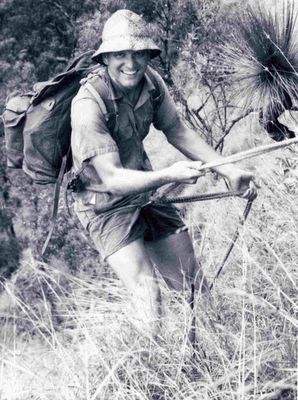

In the year that Australia pledged support to the United States in ending what appeared to be a small skirmish in Vietnam, 1962, three memorable new routes went up in the Warrumbungles—Out and Beyond, Lieben, and Cornerstone Rib. All would soon become classics and the climbers who created them—Bryden Allen and Ted Batty—would be as well-known across the country. Allen was born in Canberra in 1940, moving to England with his family when he was 11. He started climbing at age 18 when studying at London University and considers himself more of an English climber than an Australian. When he returned to Australia in 1961, he sported the latest European equipment, including a pair of climbing boots called PAs—reputedly the stickiest friction boots available at that time, taking their name from their creator, the French climbing star Pierre Allain. Over the next five years, Allen assumed the mantle of Australia’s top climber, figuring strongly in the development of climbing in the Warrumbungles, at Frenchman’s Cap, Balls Pyramid (first ascent) and the Blue Mountains. Allen described his ascent of Lieben—then Australia’s hardest climb—as ‘possibly the most foolhardy’ route he ever did on his ‘fourth or fifth weekend’ of climbing in Australia. Several climbers had eyed off the route on the west face of Crater Bluff, and the line Lieben took in particular. Russ Kippax was one of them and planned to climb the route as his swansong—but Allen beat him to it. Kippax recalls with a wry smile: ‘I wasn’t too happy about that.’ Ted Batty seconded Allen on the route wearing sandshoes and it was many years before it had a repeat ascent. Meanwhile, activity in Western Australia was starting in earnest, described in one magazine story as ‘one of WA’s newest sports’ with Latvian-born climber Arvid Miller pioneering climbing in the west.

The 1st ascent of Carstenz Pyramid

In Irian Jaya, Heinrich Harrer enlisted Russ Kippax, New Zealander Philip Temple and Bert Huizenga to make the first ascent of Carstenz Pyramid (4883m) in January 1962. The team made an additional 32 summits to their first ascent list. Kippax recalls meeting Harrer, a member of the 1938 Eigerwand first ascent team, in Sydney after he gave a talk to a Sydney Bush Walkers meeting. Harrer heard about Kippax's climbing experience and asked him to join the expedition but he would have to pay his own way. Kippax, a medical student at the time, sold his prized MGA sports car to pay for the trip without hesitation. Kippax led virtually all of the rock pitches and after the event, Harrer asked him to come on a world lecture tour. It was tempting, but Kippax decided instead to complete his studies.