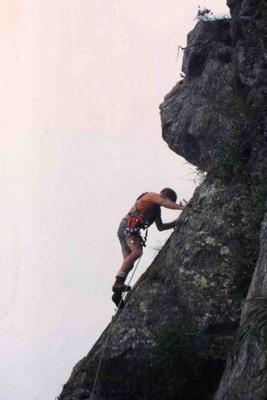

Wendy Steele and sister Katie ( closest to camera) high on the north face of Leaning Peak making the 1st female ascent, September 2003. At 410 metres, it is arguably the longest bolt-free climbing route in Australia.

This site is an archive of documents, images, interviews and other information relevant to the origins of climbing in Australia. Comments are welcome (meadowsmh@gmail.com). Text copyright 2024 M.Meadows. Copyright to photographs is held by named photographers. Please request permission to reproduce.

Challenges

ChallengesRick White returned to the Himalayas for a second time with Michael Groom in 1991 to climb Everest, but the trip ended in disarray with White having to fly home urgently to attend to a business crisis. With a long-time financier going to the wall, White was virtually forced out of Mountain Designs with huge debts. But by 2000, he was getting restless again and set up a small, hi-tech sleeping bag design and manufacturing company. In 2001, he was invited back to Mountain Designs by a new owner as adviser in research and development of new products, or, as he wryly observed, ‘as a walking historian’. His extraordinary business career had come almost full circle. It was during this period of re-adjustment that White had to confront a new and unknown challenge—a muscle-wasting illness called inclusion body myositis: ‘It was diagnosed in 1991 after I came back from Everest and I suspect I got it in 1990 after going to Cho Oyu. I definitely had it before I went to Everest because I was getting weak and then I got stronger by training but as soon as I stopped, it just went boom…really, really weak.’ For someone who had made a career out of climbing and who had played a major role in Australian climbing for more than a quarter of a century, it was a bitter blow. But his approach to this was characteristic of the attitude which propelled him into the ranks of Australia’s top climbers. White took up coaching a small group of talented sport climbers and insisted on taking part in significant milestones at Frog Buttress until his death from a brain tumour in 2004.

Picture: Rick White abseiling down Infinity at the 1998 Frog Buttress anniversary. Michael Meadows collection.

The East Pillar

The East PillarThe snow started slipping but we didn’t have axes because somehow or other Doug and George had the axes and Greg and I had hammers. But you can’t self-arrest with a hammer—you can’t belay with a hammer as Greg found out, so he got ripped off the belay and we went tumbling down. We fell 200 metres, 250. We were really lucky because there’s a col between the two peaks—Shivling’s got two peaks—and we landed in this little valley. I blacked out and woke up at the bottom and I thought, “O shit, my arms are working”—and we were fine. It all happened so fast. If we’d slid a little bit to the left we would have gone over a six thousand foot drop.Doug Scott remained a close friend of Rick White's until White's death in 2004. The 13-day East Pillar route was the most technically difficult climb ever done at altitude and remained unrepeated for 15 years.

New games: new names

New games: new names

East Barney solo

East Barney solo

It’s not technically hard but then again, with the style of the rock on those kinds of sea stacks, you can climb quickly. If you read any article written by solo climbers, it always has the same theme—the way you can focus and just flow over the rock. It’s not often you have to think about a crux move because you’ve got to have it pretty much wired in your mind and you can do it—if you have to think about it you’re likely to fall off it.

Nic and I hatched a plan to go to Mt Buffalo and simply blow everyone away by doing a hammerless ascent of Lord Gumtree. I guess we picked Lord Gumtree because it was the hardest, I had prior knowledge and we had not forgiven the uncharitable locals after our second ascent a few years earlier. Thinking back, it’s hard to justify hammerless climbing. Why make a hard aid route even harder by leaving behind some crucial gear? I guess as Lito Tejada-Flores would say it’s just another game climbers play. Pitches that were easy on pegs now became M7 and we weren’t at the crux rurp pitch yet! I led all the hard pitches with grades of M6, M7 and M8. When we finished, we ran into Roland Pauligk, whose home-made nuts had helped to solve the crux, and convinced him he should make a smaller size. Thus the RP size 0 was born.One new face on the Queensland scene was Coral Bowman. The expatriate American spent some time working with Rick White in his growing Mountain Designs business but found time to make the hardest female ascents in the country, including Insomnia and Black Light at Frog Buttress. Two years later in 1978, she was regularly climbing the hardest routes graded then at 24—and put up a new climb at Maggies Farm on Mt Maroon, Little Queen, grading it 22. Rick White teamed up with Greg Child in 1978 on the 10th anniversary of the discovery of the cliff to climb Decade, and do the first free ascent of Impulse, grading it 24. Boundaries are there to be pushed and in April that year, Chris Peisker climbed Australia’s first grade 25, Ostler, at Bundaleer in the Grampians. It was the country’s hardest climb for just five months—Kim Carrigan found Procul Harum at Mt Arapiles in September, pushing the grade up to 26.

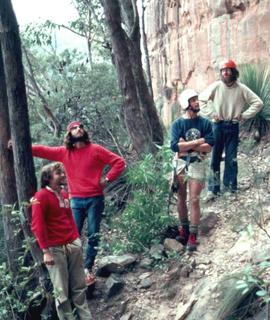

Ian Thomas (pictured) and Robert Staszewski teamed up in 1973 and almost immediately took on the hardest classics in southeast Queensland. One of their chosen climbs was a long bolt route Sid Tanner had put up through the Beerwah overhangs in the Glasshouses. It turned into an epic with them spending an unplanned, rainy night on the climb and having to bail out, leaving their gear behind on the face. The recovery process proved to be a challenge, as Thomas recalls:

It led to the singularly most dangerous thing I have ever done in climbing which was abseiling over the whole thing, tying three ropes together and tying them to small bushes at the top—because that’s all there was—and throwing it over, so there’re three rope lengths hanging down. I lurched off the top one—it was my old Miller’s rope—and the friction was incredible. And I sort of ground my way down to the overhang, dropped below the overhangs and you’re way out in space. I couldn’t obviously get back in 50 feet to get the gear so I just had to keep on going down. I went down another 20 feet and suddenly came to a knot and realised I had no idea how to get over a knot. What was this? I was spinning around and around. I didn’t have any tapes to make a prussik loop or anything like that. I didn’t know how to do it. In the end, I took off one shoe and took the lace out of it and made a little loop to stand in and then that took my weight off and I was hanging by one hand from the knot and unclipped the carabiner from above the knot. So I was hanging totally by one hand 300 feet off the ground. But my foolish mistake was that the second rope was a 9 mm and I’d only clipped in one cross crab so I basically fell the next 150 feet down onto the next knot—dong! [laughs] Squeak’s eyes were out on stalks. And mine were as well.Surviving Beerwah, Thomas eventually moved south to Mt Victoria in the Blue Mountains to run a retail outlet for Rick White’s expanding climbing business although strangely, even though it was in the thick of climbing activity there, it never really seemed to succeed. Back in Queensland, Steve Bell and Dave Kahler continued climbing new routes at Mt Maroon, Frog Buttress and the cliffs on Ngungun while more new names appeared on new route descriptions—Kim Carrigan, Trevor Gynther, Rhys Davies and Joe Friend. Meanwhile, Robert Staszewski had turned his attention to Girraween, climbing the first of hundreds of routes there he found over the next two decades.

Porter's Pass climbing meet

Porter's Pass climbing meet

Right at the lip I had to take time to place a small leeper bolt, more psychological protection than real. Surprisingly this held a fall on the first free attempt later on. Beyond that, the angle eased, and I was able to reach a small ledge about two centimetres wide. From there, the crack continued cleanly for thirty metres, just off vertical but with a rounded edge. I laybacked about ten metres up to a point where a chockstone allowed me to stand and enjoy the situation. It was an exciting lead and very committed, with a fair bit of rope drag. From there, an off width crack continued, the angle easing all the while, to the upper slope of the dome. I brought Richard up to me and we soloed up to the top. We scrambled down off the dome as the sun set, the rock glowing ruby red in the twilight. That night we downed a bottle of the local rough red and celebrated a fine climb.Over the next 15 years, around 1,000 new routes were put up there with Sullivan, Robert Staszewski, and brothers Stuart and Scott Camps involved in most of them. Steve Bell, who was active at Frog Buttress and in developing the cliffs on Ngungun, in the Glasshouses, linked up with Lesley Rivers to climb a new route, Urea Crack. Meanwhile in central Australia, Andrew Thomson and Keith Lockwood climbed 140 metres up the Kangaroo Tail on Uluru (Ayer’s Rock) before being ordered down by a park ranger.

Coomera Gorge: 1st descent

Coomera Gorge: 1st descent

I hooked up another rope and went over the edge and Dirty Don was hanging there—he’d actually unclipped himself and had wrapped his arm around the rope and that’s all that was holding him. It was a bloody long way to the deck from there—70 odd metres off the deck just hanging by his arm wrapped around the rope! I went back and started trying to organise some gear to get down to help him. A crowd had turned up by that stage and one character said, 'Get the rescue equipment, get the rescue team!' Craig turned around and said, 'We are the &*#@*& rescue team!' And he was right, we were! We were the Townsville rock and rescue team! That’s all there was and one third of the team was stuck halfway up Castle Hill about to die because he’d stuffed things up. I got down to him and hooked him up—he’d totally freaked out—and got him to the bottom. By this stage it was well and truly after dark. But Dirty Don never went climbing again.Picture: Greg Sheard in action on the east face of Maroon in 1970 shortly before moving to North Queensland. Michael Meadows collection.

Big wall battles

Big wall battles  Deep Purple on Rock

Deep Purple on RockAlan led the first pitch. To quote the guide: ‘One already feels the exposure.’ To quote me: ‘Pig’s arse!’ Second pitch, I scored. There just happened to be a tree at the start of the pitch so I climbed it. This was destined to be the first of a long series of botanical aids on the climb. Belay in tree. Alan followed up (with pack on back), swinging through the trees like a constipated Tarzan.And so it continued: Millband grabbed a snake on the crux pitch and Sheard managed to climb it free on a toprope, finding the ‘rotten’ tree to be ‘as solid as buggery’. Greg Sheard had once again dealt a body blow to any romantic notions of big wall climbing on Mt Barney!

Initially there was the absurd interstate rivalry between Victoria and New South Wales and Victoria and Queensland and a lot of that was due to the lack of contact. It was childish on all sides. I suppose it was taken seriously and the letters would fly back and forwards through Thrutch and that would trigger it off. And there’d be raiding parties down to free Victorian routes or free NSW routes or whatever it was...While much of the debate through the pages of Thrutch was tongue-in-cheek, it got to a point where bitterness began to creep into the exchanges. White recalls the impasse: ‘There was a point in time where I made a decision never, ever to write another article—ever! I didn’t break that pledge until probably around 1996 when Chris Baxter talked me into writing a history of something or other for Rock magazine. So I didn’t write anything from probably 73 onwards.’ Eventually, Victorian climber Nic Taylor who was working with White's company, Mountain Designs in Brisbane, was instrumental in bringing them together in the late 1970s and they subsequently became good friends.

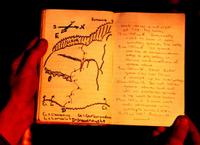

The 1st Frog Buttress guidebook

The 1st Frog Buttress guidebook

Although still very much a male-dominated world, talented 16 year old Marilyn Dall (pictured left) joined with ‘veteran’ Pat Prendergast in 1969 to put up the first all female climb at Frog Buttress. They called it Revolution, perhaps celebrating the year in which Australian women finally received equal pay for equal work—in theory, at least. The most novel ascent at the Buttress and perhaps anywhere in Australia that year was Macraderma. All 35 metres were climbed entirely underground! Paul Caffyn and Rick White abseiled to the bottom of the cleft and with White unable to get off the ground on the damp, slippery rock, Caffyn took over. Applying his considerable caving skills, Caffyn managed to solve the difficult start. Ian Cameron abseiled in to join White at the bottom and they both were forced to prussik up the first 10 metres, unable to follow Caffyn’s inspired lead. Another significant ascent that year was the hard aid climb, Brown Corduroy Trousers, climbed by Rick White and Ian Cameron. Thirteen years later, Kim Carrigan would climb it free, grading it equal to Australia’s hardest climb at the time—28. Along with the new routes at Frog Buttress came another wave of new climbers—Barry Overs, Steve Bell, Dave Kahler, Chris Knudsen and Alan Millband.

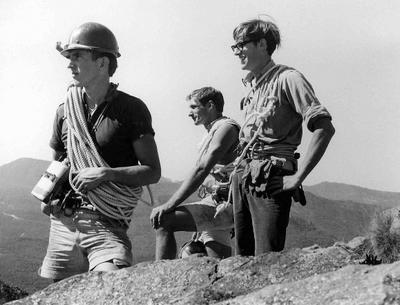

In August 1968, the Brisbane Rockclimbing Club became the first in Australia—after the Sydney Rockclimbing Club—to adopt John Ewbank’s open-ended numerical grading system. Following the discovery of Frog Buttress, Rick White, Chris Meadows and Greg Sheard decided to head south in January 1969 to sample grades of climbs in the Blue Mountains and to sharpen their jamming skills. They spent a week at Mt Piddington (Wirindi) and Narrow Neck, climbing 18 routes, including the imposing Amen Corner and Flake Crack. With Queensland virtually a bolt-free zone, the sight and frequency of bolts on all manner of climbs appalled them, as Greg Sheard recalls: ‘There were bolts everywhere and we decided to chop a few. We would never chop them unless we could find alternate placements for equipment.’ The real fun began when they turned up at a Sydney Rockclimbing Club meeting at the Hero of Waterloo Hotel in Sydney and were confronted by the Safety Officer, demanding to know which climbs had been affected. Chris Meadows took exception to his officious approach, as Sheard relates: ‘He was going to have a severe discussion with this guy’s head using both of his fists.’ After dragging the two apart, White and Sheard decided to come clean. ‘He got angrier and angrier when we told him how many we’d done,’ Sheard laughs. ‘We did do a fair few. I suppose we did get a bit carried away because it wasn’t exactly clean the way we pulled some of the bolts out.’ Despite John Lennon’s urging that we should all Give Peace a Chance, the Queenslanders’ brash approach reflected a growing interstate rivalry in Australian climbing circles—albeit most of it good-natured. As Frog Buttress became better known across the country, an intense propaganda war broke out through the pages of Thrutch, with each State claiming to have the best cliffs and the hardest climbs at some stage or other. But it all seemed to come down to Victoria versus the rest.

We complemented each other well and several times on new routes I would figure out the technical moves only to back off and have Rick punch the route through to the finish. More often we were friendly rivals and I usually was the first one to repeat Rick’s new routes at Frog, although Barry Overs filled this role for a while. I realized, too, I needed to lead new routes independently of Rick to establish my own style so we never became regular partners but helped push each other locally, although Rick was more driven by the achievements of John Ewbank in the Blue Mountains. My first climb with Rick and also my first introduction to Frog Buttress was on the first ascent of Infinity...

'Paradise found'

'Paradise found' The fall factor

The fall factorI think I’d already had a serious fall there—a head-first plummet off By Ignorance after getting on the wrong route. Mal Graydon was belaying and actually saved my neck because I did actually touch the ground with my helmet. Mal had done a static belay but had also jumped backwards and my first peg had pulled out but the next one took it up. If he hadn’t done either a static belay or made a jump backwards, I would have been dead.The sight of Greg Sheard, curled up in a ball, plummeting head-first towards the ground became a common one at the Kangaroo Point cliffs. He continued to push the limits and seemed to lead a charmed existence. But it couldn’t last and he managed to break an ankle—and, as he discovered years later, a vertebrae—in a 10 metre fall at Kangaroo Point while trying to free an aid climb started by a rival. But this didn’t stop Sheardie who quickly discovered crutches are very good at bashing a pathway through lantana en route to Glennies Pulpit or as a stabilising prop abseiling down Caves Route on Tibrogargan. Sheardie had emerged as the character of the late 1960s—a very strong climber, with an unconventional approach and an ability to create havoc, in the nicest possible way. Like his ankle and vertebrae, his infamous black Hillman also came to grief when one 'friend' painted fascist slogans all over it and another 'friend' then dropped an 80kg belay weight from the top of the cliff onto the boot, almost piercing the petrol tank. But it was all in good fun and at least he was still able to drive it to the wreckers next day!

Leaps of faith

Leaps of faith And the women?

And the women?Although climbing in Queensland (and the rest of Australia) in the late 1960s was largely a boys’ club, several women had been active on the climbing scene in Queensland since the mid-1960s. Pat Prendergast (pictured) was the first woman to join the Brisbane Rockclimbing Club in November 1965. She was also the first woman to lead Carborundum on Tibrogargan and made one of the first female ascents of Desperation Wall in 1966. But the lure of the New Zealand Alps was too great and she left Brisbane, making several return trips over the years. But most of her life has been spent climbing and drawing the mountains she loves, publishing a book of her paintings. From February 1968, Marion and Sue Speirs, along with Lesley Rivers, were regular climbers who mixed their activities on the rock with bushwalking. But like Pat Prendergast, they, too, were attracted to snow and ice climbing in the high mountains of New Zealand. In December 1968, Marion, 26, and Sue, 21, went missing in the Southern Alps for three days, caught in a freak storm while climbing in the Malte Brun Range in New Zealand. Their survival skills were acknowledged by the Chief Ranger at Mt Cook who believed no one had ever been rescued before after having been on the mountain for so long—74 hours. Another strong, enthusiastic climber-bushwalker Lesley Rivers was a regular at Kangaroo Point and on crags around southeast Queensland in the late 1960s. She was the first woman to climb East Crookneck with Greg Sheard in 1969 and like others before her, was eventually drawn into mountaineering, first in New Zealand, then the European Alps. She was killed in an accident on the Jungfrau, in the Swiss Alps, going to the aid of an injured climber, in the 1980s.

In high places

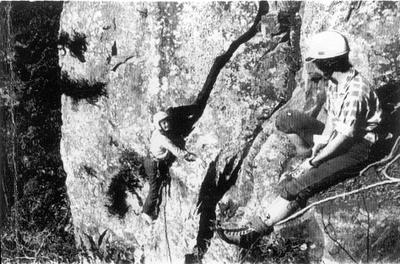

In high placesRick White, climbing with Dave Reeve, found the first route up the big east face on Mt Maroon in February 1968. They called it Deception I—a bold and circuitous 250 metre climb through a maze of loose blocks, clifflines, caves and corners. The following weekend, John Shera (pictured), my brother Chris and myself climbed the North Face of Leaning Peak. We were forced to bivvy on a ledge about 60 metres from the summit, completing the climb the following day. At 410 metres, it is the longest climb in Queensland and amongst the longest in Australia. With three of the biggest faces in southeast Queensland now climbed—the East Faces of Mt Barney and Mt Maroon and the North Face of Leaning Peak—attention turned to other problems, other lines. For the first time since the early 1950s when Kangaroo Point had been used as a top-roping and training cliff, climbers led the first hard routes there—Cais started the deluge with a bold lead of Cox’s Overhang in January. White followed with Nightfell and the classic, Adam’s Rib. Cais found Tombstone Row and four weeks later, the hardest climb on the cliff: the fiery Pterodactyl. The status of the Kangaroo Point cliffs had changed significantly and a hard core of new climbers had emerged.

New waves

New waves